Latest Updates About Vaccines and COVID-19

Call Today to Schedule Your Vaccine Appointment: 601.663.1213

This public messaging is supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of an award totaling $99,058.00 with 0% financed with non-governmental sources. The contents are those of Neshoba General Hospital and Clinics and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by HRSA, HHS, or the U.S. Government. For more information, please visit HRSA.gov.

Visitation Policy

*This policy will stay in effect until further notice and is necessary

due to the Delta surge in our facility.

Dr. Jon Boyles needed an intensive-care unit. His patient was critically sick with COVID-19. Others filled his emergency department at Neshoba County General Hospital, but this one was well beyond his capacity for care. The patient’s oxygen saturation declined enough for him to put them on a ventilator. But without an intensive-care unit and the staff to support his patient, slowly drifting away, Dr. Boyles knew he was treading water. Later, when Boyles spoke to the Mississippi Free Press, last night after the end of his shift, his voice was nervous, filled with exhausted energy. He was run down and out of breath. He told the story of a single patient and the whole pandemic at once. After ventilating the patient, he started, as always, by reaching out to the two major hospitals in Meridian, the first port of call for a Neshoba County transfer when times are good. They had nothing for him, no room for a critical patient. No surprises. Earlier in the week, when the doctor had called the same hospital, Boyles was told they’d be glad to take the patient—as long as he sent some nurses along with them.

Boyles explained to the Mississippi Free Press. “It’s directly connected to MED-COM,” a 24-7 communications center at the University of Mississippi Medical Center that has helped sort out the complicated ebb and flow of patient transfers. “You don’t even have to dial it. It was always there. We counted on it,” he said. “When you’re in a small, rural place, no space left, and you have somebody critical, or a trauma patient, you could always pick up that phone, and in the past you could count on them doing everything they could to help you. Now when you pick it up they tell you, sorry, everybody’s full. Good luck.”

So it goes. Boyles’ emergency room was swarmed, with COVID and a lot more. “Anything in the world can walk in the emergency department. We’re a tiny rural hospital,” he said.

The four-story Neshoba County General Hospital has a 12-bed emergency department, is open 24/7, and in the days since Christmas, the capacity has been full to bursting. “It’s on the edge of what we can handle. Some days people leave without being seen.”

Boyles spends his shifts putting out fires, the most he and his team can do given the circumstances. He checked his critically ill patient, watched their oxygen saturation, the motions of keeping a deeply ill person stabilized. “They need a pulmonologist,” he said. “They need ICU nurses, with a different skillset. We don’t have specialty nurses.”

Whenever he could, Boyles was back on the phone. “We couldn’t get that patient transferred anywhere in the state,” he said. “I called literally every hospital. I ended up calling hospitals in Tuscaloosa, Birmingham, Mobile, Memphis. Nothing. Everybody says they’re on bypass.”

The clock was ticking. The omicron surge, for our many triumphant declarations that it is milder in hospitals, was not treating the patient so mildly. In fact, it may not have been omicron. It may very well have been delta. Boyles will never find out. His job is not to interrogate. His job is to keep the lights on.

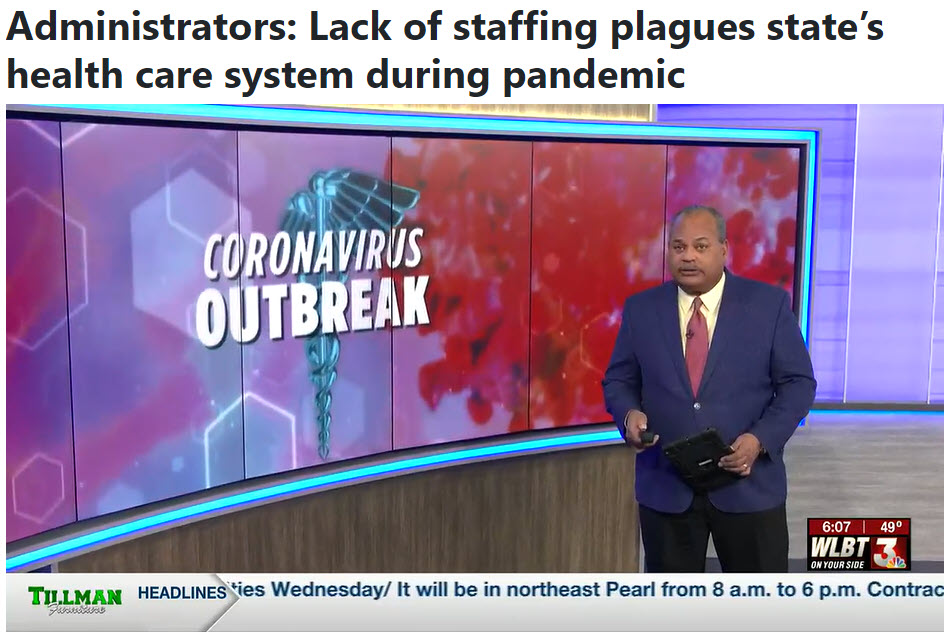

No, no, no. No room. No beds. No staff. A shortage of medical personnel is the real issue, for which all talk of beds and capacity is a euphemism. Mississippi bleeds nurses to the wealthy poles of health care, to Texas, to New Orleans. UMMC, the state’s medical titan, struggles. Smaller outlets and critical access hospitals one rung down the ladder languish.

For much of Boyles’ shift, the emergency-room director was a substitute phone operator. He called, he waited, he lamented the repetitive no—he watched the patient, balanced delicately above the void, in need of treatment he simply could not provide. More fires cropped up around him.

“During this whole time, we’re overwhelmed. We’re getting flooded with COVID patients. The waiting room is backing up,” he shared with this reporter. He stopped counting somewhere after 20 calls, took a deep breath and exhaled. Jon Boyles was 10 hours into a 12-hour shift, and his patient had nowhere to go.

‘It’s a Free-For-All’

This stage of the pandemic, for many of Mississippi’s rural hospitals, is structurally different from anything that has come before. Before, in the early surges, and in delta especially, it was worst in the flagship hospitals—UMMC, Baptist, Singing River—inundated by swells of the critically sick. With delta, ICUs spilled out into field hospitals, such was the burden of severe COVID.

This is something else—not a tsunami, but a river slowly rising. Of course, omicron swarms hospitals with COVID patients like every other variant, but in aggregate the symptoms are not as horrendous, the clearance time is shorter. On this, the rural hospital workers who spoke to the Mississippi Free Press for this story agreed.

But the state of the hospital system, especially on the periphery, is significantly worse. A North Mississippi hospital director, who spoke to the Mississippi Free Press on background, explained that the cracks in the system have grown over the pandemic and that omicron was exploiting them.

“I’ve never seen anything like this in all my years of care. I’ve thought a lot about (how this surge compares) this week—I had minimal staff who contracted the virus in the first wave. Now, with omicron, there’s no containing it. It’s an uncontrollable wildfire,” the director said.

The nursing workforce is hit hard, the director explained. “We’re not working together anymore. All of these larger systems are paying more. I was told (Ochsner Medical Center) in New Orleans is paying travel nurses $200 an hour.” Their small hospital had only lost three nurses—a burden, but still significantly less than some of Mississippi’s other care centers.

Travel nursing siphoning qualified professionals is only part of the problem. The pandemic has burned out medical staff across the nation, killed many others, primarily nurses and support staff, and now in the short term omicron has kicked the bottom out of the health-care system. It is taking swathes of professionals out of commission when the system is already weakened, and with more patients flooding in.

Mississippi nurses have cried out for help, identifying a coming lack of staff and support that has now materialized. Requests from the state’s medical community for emergency action to staunch the bleeding have gone unheeded.

“This is a crisis that won’t wait until we have workforce development six months, a year from now,” Susan Russell, chief nursing officer at Singing River Health Systems, told Mississippi Today’s Sara DiNatale in November. “People’s lives are being put into jeopardy right now.”

Across Mississippi and across the U.S., stress fractures buckle the framework of care. The structure is standing, but the metal is screaming.

Lee McCall, the CEO of Neshoba County General Hospital, explained the shift in an interview. “You focus on the outcomes,” he said.

“Thus far, I don’t think we’ve had a system failure. I think we’ve had good patient outcomes, we’ve cared for our communities. We cared for public health. This time around we’ve lost staffing, and therefore the capability to staff up the beds that the system displays.”

The result is, effectively, the weight of the pandemic without any of the unity and organization of the pandemic response. “It’s a free-for-all. You have to find the next bed available by calling and praying,” McCall added.

The Mississippi State Department of Health ostensibly tracks the available hospital and ICU capacity around the state. As of today, that tracker shows a visible decline in available ICU beds since the beginning of the omicron surge, but also suggests that 52 remain available in the state. When the Mississippi Free Press shared these numbers with the hospital administrators and physicians interviewed for this story, they were utterly baffled.

If the state had the capacity for over 50 more critically sick patients, McCall asked, then why would they be sending patients out of state? “We contacted every hospital (in Mississippi) yesterday,” McCall said. No room.

MSDH Considering Transfer Plan

At an MSDH press event this afternoon, Director of Health Protection Jim Craig shed light on the realities of Mississippi’s critical care landscape.

“Right now, hospitals are reporting 47 ICU beds available. Now, of those 47 ICU beds, that includes some of our long-term acute care facilities,” Craig explained, referring to facilities that tend to take ICU discharges, mostly unsuitable for the most critically sick patients needing transfers.

“Only 11 of those beds are in our larger facilities, in level one and level two hospitals. There is a need for additional ICU space in different areas of the state,” Craig added. “Because it’s more than just COVID. It’s trauma, heart attacks, strokes, and other critical injuries and illnesses still part of the critical transfers needing to be moved around in the state of Mississippi.”

The consequences of the ongoing staff shortages have severely limited capacity across the state and far beyond. Craig said. “We understand that when ICU beds are still available, many of them cannot be opened due to a lack of staffing. We have received some reports recently that some hospitals have been unable to find ICU spaces within the state, and at least a couple of patients have had to move out of state in their transfers.”

“The COVID system of care plan is still active in the State of Mississippi, but the mandatory rotation of critical patients is not currently active,” Craig said. It is this mandatory rotation, instituted during the delta surge, that took some of the burden off of ER physicians like Boyles, and administrators like McCall. “We have been working with our partners at Mississippi MED-COM on a focused system of care for the most critically ill, in the event that there is a need for it.”

In short, Craig explained, the limited rotational system that may be implemented in the future would allow for MED-COM to elevate critical patients from hospitals, like Neshoba County General, to settings more appropriate for their needs. Whether that will be sufficient to stem the rising tide remains to be seen.

‘Delta Broke The Health-Care System’

Dr. Jonathan Wilson is the chief administrative officer for the University of Mississippi Medical Center, as well as incident manager for the hospital’s COVID response, roles that give him broad responsibility over the MED-COM system.

“When we’re not in a pandemic or any other disaster, MED-COM coordinates ER transfers in UMMC for rural hospitals, and coordinates our air and ground ambulances,” in addition to other duties, Wilson said. “The other piece is the emergency support function. Primarily, you think about sending in teams after a tornado or hurricane for casualty collection, triage, that sort of thing.”

That system evolved during the pandemic, Wilson explained, putting MED-COM to the task of supporting MSDH with the entire state’s system of care, including patient transfers.

“The system of care is (still) in place, but the rotation and the close tracking has not been activated as of yet. So we’re kind of in limbo right now,” Wilson admitted. In limbo, as the waters rise, and facing a much-reduced capacity overall. Wilson’s assessment of the entire health-care landscape is unsparing.

“Earlier this morning, UMMC had 10 or 12 patients waiting on an ICU bed. And so the same frustration that a rural ER has, our ER has. Because they can’t get an ICU patient placed either. It’s not just a single hospital,” Wilson explained. “It’s not a certain part of the state. It’s everybody, unfortunately. We get calls from Louisiana and Alabama. Last night, we got a call from Texas wanting to try to place the patient over here. It’s not just a Mississippi problem.”

When MED-COM’s rotational capacity is reactivated, they will go back to work for providers like Dr. Boyles, incapable of creating new space and new caregivers, but equipped to sand down the roughest spikes, to elevate the most difficult cases across the state where they are better served.

For now, any attempt to quantify the remaining ICU capacity across the state is doomed to fail. “Not all hospitals have the same capacity to care for certain or acute conditions,” Wilson said. “Some kinds of patients—needing cath labs, with strokes or multi-system trauma, the ones who need neurosurgical coverage … that’s what we’re trying to focus our efforts on right now.”

Wilson and other medical professionals see the system fracturing. What the rest of the state has—the numbers, the charts, the promise of empty beds—simply cannot reflect the realities of hospital care in 2022.

“Before the delta wave, we had a bunch of press conferences and we told everybody that would listen that the health system in the State of Mississippi was at the breaking point,” Wilson said. “Well, delta broke the health-care system in the State of Mississippi. It is still broken. The state as a whole just hasn’t recovered from it. And it may take years for us to get staffing back to where it was pre-delta. That’s just the reality we’re all having to live in right now.”

‘The Day We Dreaded’

By the time Dr. Boyles’ patient got a transfer, it was midnight, six hours after his shift ended.

A paramedic and two medics piled into an ambulance for one of the longest land-transfers Boyles’ ER has ever dispatched.

“We ended up having to ship that patient to Pensacola. To Florida. That’s a terrible situation,” Boyles said. “We’re a small county hospital, and now we’ve tied up an ambulance and three medics for a whole shift.”

It would be 10 hours before the personnel would return, bleary-eyed from the overnight journey and the process of checking the patient in. But they made it. The hospital’s care and a telemarketer’s shift worth of phone calls had given them a shot.

“Across the whole state, beds are becoming less and less available,” Boyles explained. “We were so fearful in the beginning of COVID about this surge that was going to come and overwhelm the healthcare system. Everybody stepped up and it seemed like we stayed ahead of it.”

Years of fighting wave after wave, anticipating the vaccine, hoping for a reprieve. Now, those bonds are frayed, Boyles said. “Surprisingly, it’s in the last few days that I think we’re about to hit that point. When I had that critically ill patient and I was running out of options, I spoke to the doctor on call. The first thing I said was that the day that we’ve dreaded for two years is finally here.”

“It feels like the dam is full,” Boyles said, “and it’s springing leaks.”